Distributed Web of Care

Accessibility Dreams

by Shannon Finnegan, DWC Artist in Residence

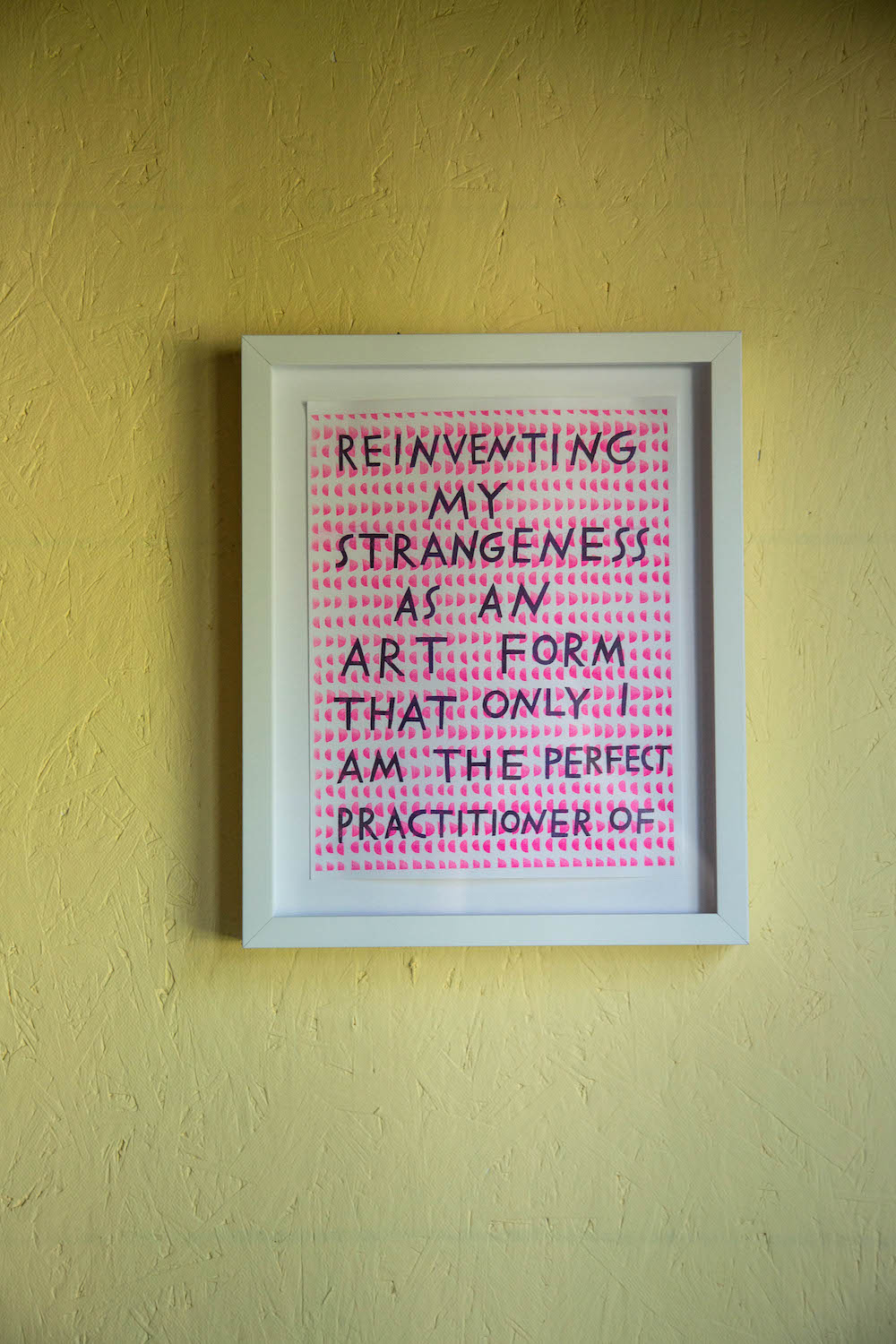

Image description: A framed print reading, “Reinventing my strangeness as an art form that only I am the perfect practitioner of.”

Image description: A framed print reading, “Reinventing my strangeness as an art form that only I am the perfect practitioner of.”

The qualities of any action or tool that aims to create accessibility communicates the creator’s assumptions about disabled people — not only in terms of its logistics, but also in terms of its personality, tone, and style. Accessibility measures continually fail to treat disabled people as complete human beings, prioritizing a checklist of ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990) compliance over the interests, nuances, desires, and comfort of those using the space.

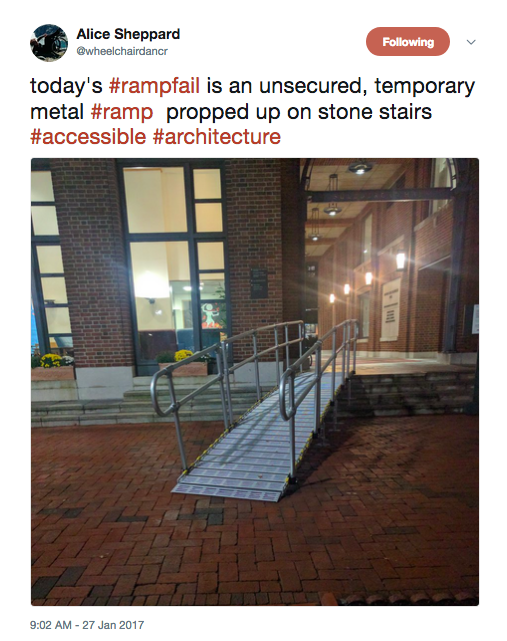

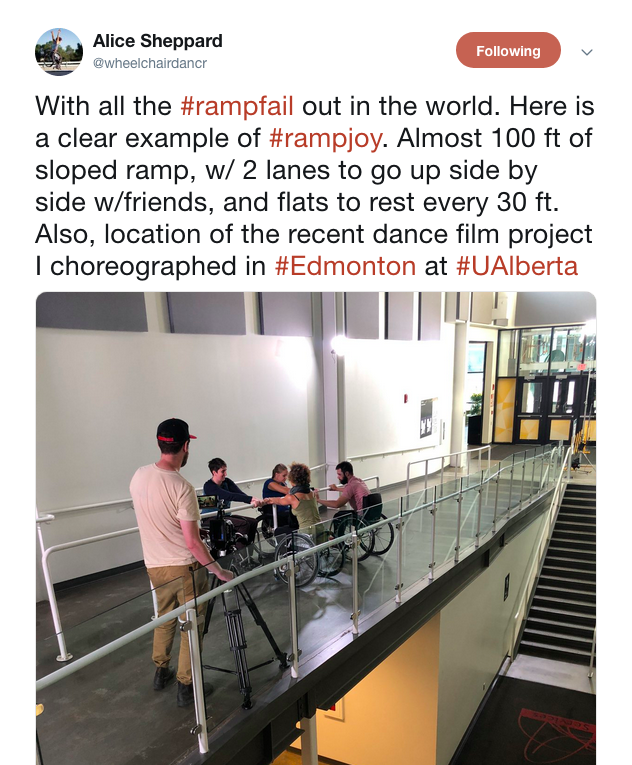

Compare the examples in tweets hashtagged #RampFail and #RampJoy. #RampFail has lots of examples of uninspired access — scenarios where someone has gestured toward accessibility, but missed the mark. #RampJoy shows how access can become a source of delight and a part of disability culture.

Image description: A temporary metal ramp is set on a set of four steps. The ramp doesn’t look safe or integrated into the space. The associated tweet by @wheelchairdancr reads, “today’s #rampfail is an unsecured, temporary metal #ramp propped up on stone stairs #accessible #architecture”

Image description: A temporary metal ramp is set on a set of four steps. The ramp doesn’t look safe or integrated into the space. The associated tweet by @wheelchairdancr reads, “today’s #rampfail is an unsecured, temporary metal #ramp propped up on stone stairs #accessible #architecture”

Image description: 4 dancers in wheelchairs face each other holding onto a metal railing with 50 feet of ramp going uphill and downhill on either side of them. A camera person shoots footage nearby. The associated tweet by @wheelchairdancr reads, “With all the #rampfail out in the world. Here is a clear example of #rampjoy. Almost 100 ft of sloped ramp, w/ 2 lanes to go up side by side w/friends, and flats to rest every 30 ft. Also, location of the recent dance film project I choreographed in #Edmonton at #UAlberta”

Image description: 4 dancers in wheelchairs face each other holding onto a metal railing with 50 feet of ramp going uphill and downhill on either side of them. A camera person shoots footage nearby. The associated tweet by @wheelchairdancr reads, “With all the #rampfail out in the world. Here is a clear example of #rampjoy. Almost 100 ft of sloped ramp, w/ 2 lanes to go up side by side w/friends, and flats to rest every 30 ft. Also, location of the recent dance film project I choreographed in #Edmonton at #UAlberta”

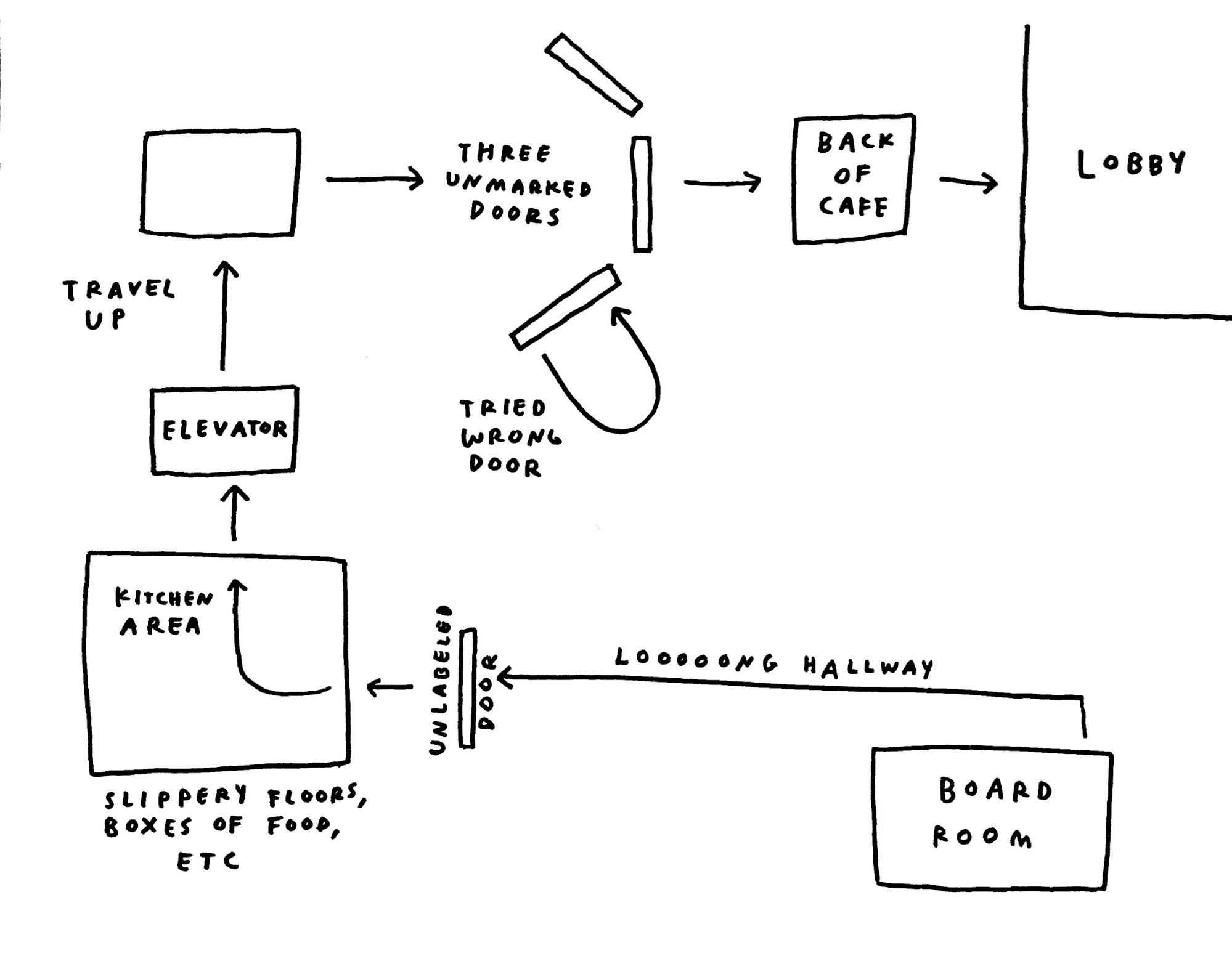

Now, let’s look at the “accessible” route to the Ace Hotel New York’s boardroom, where the Distributed Web of Care skillshares took place. This route is a prime example of uninspired, compliance-oriented access. This route was clearly designed by an architect to meet code and then never considered again. The route reveals not only the vast limitations of the ADA, but also reflects the architect and building owner’s lack of attention to disabled visitors.

Image description: A simple, hand-drawn diagram showing my memory of the route from the boardroom to the lobby. Features include: loooooong hallway, multiple unmarked doors, a kitchen area, and the back area of a cafe.

Image description: A simple, hand-drawn diagram showing my memory of the route from the boardroom to the lobby. Features include: loooooong hallway, multiple unmarked doors, a kitchen area, and the back area of a cafe.

While I am extremely grateful for the protections of the ADA, it should never be considered a template for accessibility, as is obvious from the “accessible” route to the boardroom. The route is very indirect — a classic problem with “accessible” routes. This may work okay for some wheelchair users, but presents problems for lots of other people. Imagine someone using a walker. Likely, the the stairs aren’t an option for them but neither is walking a long distance to get to the elevator.

In addition to it’s logistical failures, the route conveys volumes about the business owner’s understanding of their disabled visitors. The route has no signage and goes through many back-of-house areas. There is nothing about the route that communicates that the hotel thought an actual human would travel it, much less a human they want to delight and welcome to their hotel.

Image description: Distributed Web of Care Skillshare participants being lead through the Ace Hotel’s accessible route.

Image description: Distributed Web of Care Skillshare participants being lead through the Ace Hotel’s accessible route.

Access is complex. I went to a talk in 2017 by scholar Simi Linton where she said access is often “expensive and disruptive.” We are all operating with limited money, time, and capacity to organize, but I am disappointed by how often people and institutions miss opportunities to do better, even if in small ways.

In addition to providing much needed wayfinding, a fun sign along the “accessible” route would go a long way toward communicating “We see you, we expected you, we understand not only are you someone who needs an elevator, but you also enjoy fun and interesting things.” A sign is far from a complete solution, but it’s a little better.

In my art practice, I think about how we can move towards better and more nuanced approaches to access. Instead of focusing on compliance and doing the minimum, what if we approach access creatively and generously, centering disability culture? How do we make spaces and experiences that disabled people not only can access, but want to access?

Image description: An orange wall with big text in a stair-inspired font that says, “Anti-Stairs Club Lounge.”

Image description: An orange wall with big text in a stair-inspired font that says, “Anti-Stairs Club Lounge.”

In 2017, I created an installation for the Wassaic Project called Anti-Stairs Club Lounge. The Wassaic Project’s exhibition space Maxon Mills is inaccessible: seven flights of stairs, with no ramp or elevator access above the ground floor.

Anti-Stairs Club Lounge is a space exclusively for visitors who cannot or choose not to go upstairs. You get the passcode to enter the lounge by signing a form at the front desk certifying you are not going upstairs in the mill. Inside the lounge, there is seating, reading materials, chilled seltzer, candy, artwork, and a charging station.

Image description: The interior of the lounge featuring chairs, reading materials, lamps, candy, and a mini-fridge.

Image description: The interior of the lounge featuring chairs, reading materials, lamps, candy, and a mini-fridge.

I created the lounge as a way to highlight the inaccessibility of the exhibition space while also adding to disabled visitor’s experience of the exhibition space. I designed the lounge with lots of fun details — custom cushions printed with the Anti-Stairs Club Lounge logo, a stair-themed clock face I made out of sculpey, books that I have found helpful in understanding my identity as a disabled person. I painted a wall mural that reads “The higher you climb, the farther you fall” to add a humorous touch to the anti-stairs ethos of the space.

The Wassaic Project has a long way to go to becoming an accessible space. As one disabled artist, I am not interested in (nor am I necessarily trained to) help make those changes. There are accessibility consultants who have expertise in all the details of creating an accessible space. But my hope is that Anti-Stairs Club Lounge pushes people to recognize that things need to change and that change can come in many forms.

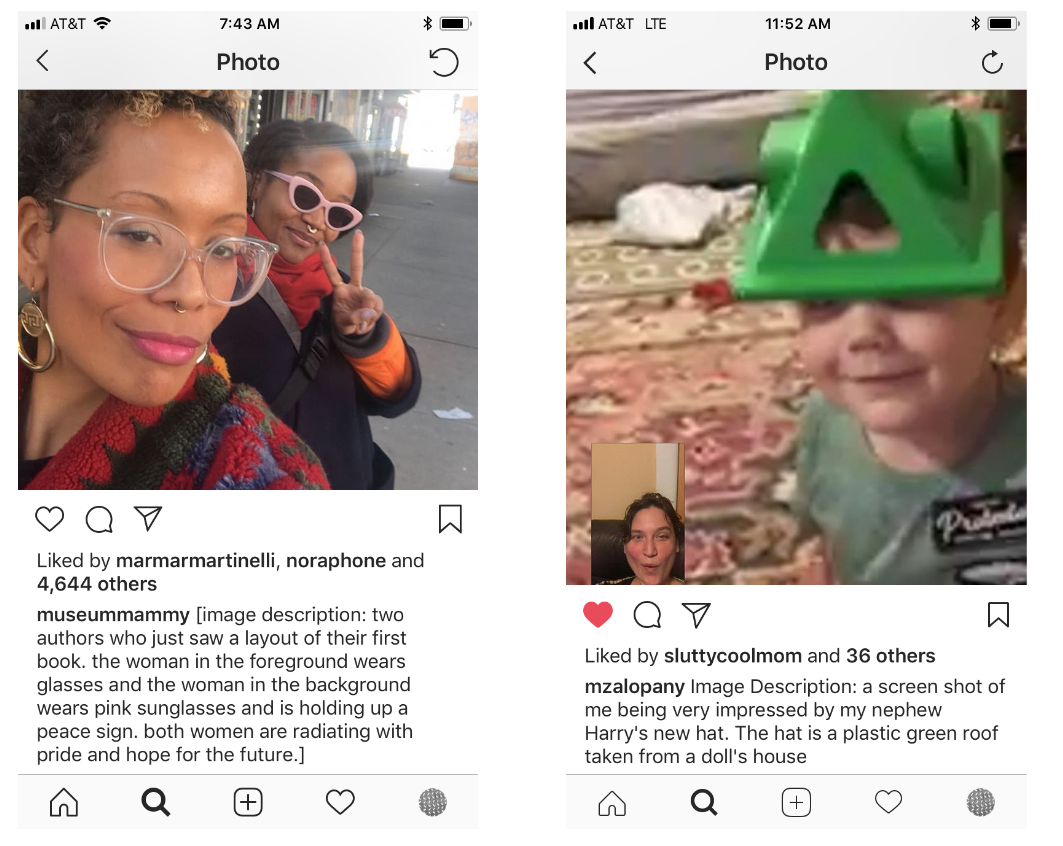

Image description: On the left side, a screenshot of an Instagram post by @museummammy. The photo is describe in the caption as “two authors who just saw a layout of their first book. the woman in the foreground wears glasses and the woman in the background wears pink sunglasses and is holding up a peace sign. both women are radiating with pride and hope for the future. On the other side, a screenshot of an Instagram post by @mzalopany. The photo is describe in the caption as “a screen shot of me being very impressed by my nephew Harry’s new hat. The hat is a plastic green roof taken from a doll’s house.

Image description: On the left side, a screenshot of an Instagram post by @museummammy. The photo is describe in the caption as “two authors who just saw a layout of their first book. the woman in the foreground wears glasses and the woman in the background wears pink sunglasses and is holding up a peace sign. both women are radiating with pride and hope for the future. On the other side, a screenshot of an Instagram post by @mzalopany. The photo is describe in the caption as “a screen shot of me being very impressed by my nephew Harry’s new hat. The hat is a plastic green roof taken from a doll’s house.

Digital and physical access have interesting parallels. I am currently a resident at Eyebeam where I’ve been thinking about creative ways to write and present alt-text (image descriptions for blind and low vision people who use screen readers). I want to move alt-text from the realm of compliance to a space of exploration and experimentation. Alt-text has the potential to be a form of poetry, a process where people put care into the way they use language. This project is a starting point for imagining an internet that prioritizes disabled people’s interests, desires, inclusion, and delight.

I’m hopeful that the ways we approach access as a society will continue to expand and evolve. We need to focus on centering disability culture and acknowledging the complexity and nuance of disabled people. I know this will not happen without the presence of disabled people as designers, artists, thinkers, leaders, and creators. As disability activist and designer Liz Jackson says, “Whatever you do, don’t commit to disability—commit to disabled people.” So look around at the spaces that you occupy (both physical and digital) and observe who’s there and who’s not. Where are there indirect routes, obstacles, misleading signs, and barriers that keep people out of those spaces?

Suggested Readings

- Social model of disability intro

- An Accessibility Manifesto for the Arts by Carmen Papalia

- Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice by Mia Mingus

Questions

- Are there any questions that came up from the readings? Passages or ideas that stood out?

- When have you noticed steps being taken toward access in your life? This could be at your job, at events you attend, as you move through the city, in your social circles, etc. Do you have any thoughts about the quality or characteristics of that access?

- What are some ways we can advocate for access?

Credits

This essay is based on a skillshare by Shannon Finnegan on July 15.2018 at the Ace Hotel New York. It’s been edited by Shira Feldman and published on January 30, 2019.

About the author:

Shannon Finnegan is an artist whose practice involves a mix of drawing, design and writing. Her current motto is “Reinventing my strangeness as an art form that only I am the perfect practitioner of.” She’s created Anti-Stairs Club Lounge, Disability History PSA, and other projects about disability culture and access.

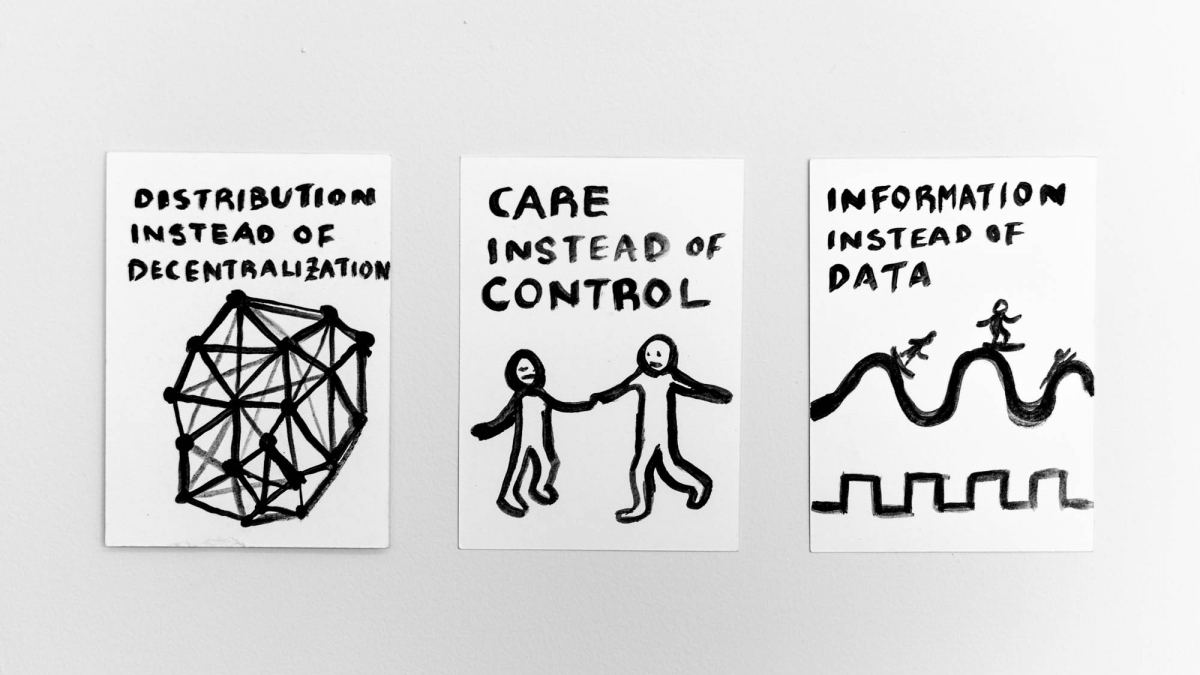

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care